aAlthough buy Inflation-protected bonds to protect against inflation do not seem unreasonable; it would have been a spectacularly unprofitable move during the most recent period of inflation. A hundred dollars put into inflation-protected government bonds in December 2021, when investors first saw core U.S. inflation rise to 5%, would have been worth just $88 a year later. Even cash under the mattress would have done a better job.

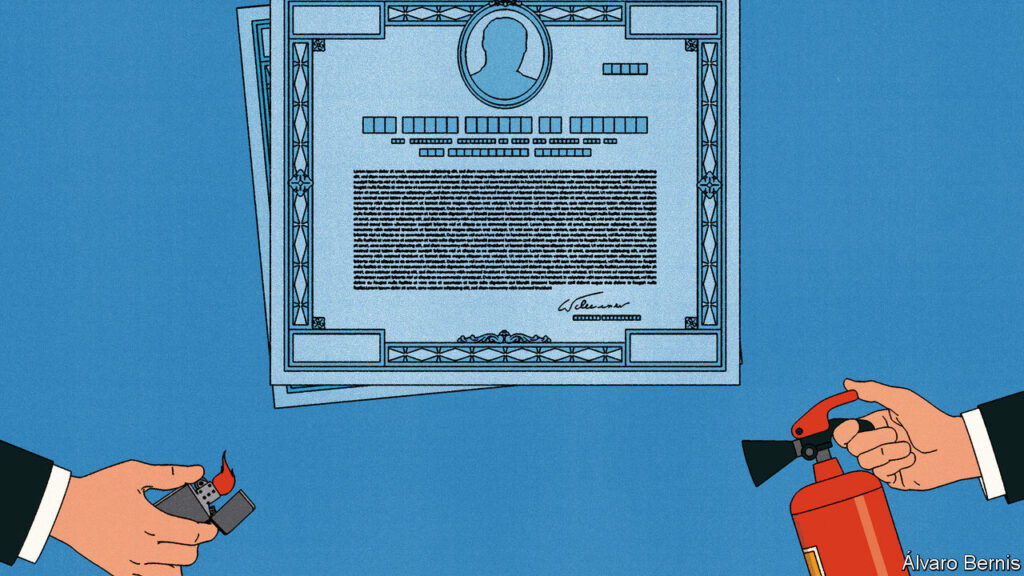

It’s safe to say that inflation-linked bonds are in trouble. Investors pulled $17 billion from exchange-traded funds linked to it last year. Canada has announced plans to end its issuance in 2022; Germany did the same in November. Sweden is considering its options. Yet these countries are making a mistake. As long as their purpose is not misinterpreted, inflation-linked bonds serve a crucial function for the markets and the governments that issue them.

Why don’t bonds always offer protection against inflation? Start by breaking down the sources of return for a bondholder. First come coupons, payments received before a bond matures. The difference between inflation-linked bonds and their conventional counterparts is that they are not denominated in dollars, euros or pounds; instead, they rise with inflation, just like the bond’s principal. Their real value is preserved if inflation is unexpectedly high. So far inflation-protective.

However, a second mechanism will be important to many investors: changes in the price of a bond. Such changes reflect shifts in the market value of the future payments to which a bondholder is entitled. This is where a catch arises. The real interest rate determines the present value of that future money: when interest rates rise, bond prices fall. And as 2022 and 2023 made painfully clear, few forces raise long-term real interest rates as sharply as a central bank sharply tightening monetary policy. Typically, this second mechanism is more important for inflation-linked bond returns than the first. Indeed, it is the cause of the $12 loss an investor would have suffered between December 2021 and December 2022.

Although they do not always protect against inflation, the bonds do serve a broader purpose. For markets, their main value is to isolate (and price) beliefs about economic concepts. Conventional bond yields combine two different forces: inflation expectations and real interest rates. Inflation-linked bonds untangle these: their yields more clearly reflect the market’s pricing of real interest rates. Similarly, the difference in yield between a nominal bond and an inflation-linked bond reflects the market price of expected inflation, known as “break-even inflation.”

Separating these concepts is important. For speculators, this means an easier way to trade under macroeconomic pressure. For market observers, making real interest rates visible and tradable helps explain the pricing of virtually every other financial asset. One way to view stocks, bonds, and real estate is as a way to purchase future payouts (dividends, coupons, and rent, respectively). Both have real interest rates anchored in the price. And for central bankers, breakeven inflation provides a constantly traded measure of whether markets find their inflation targets credible.

In fact, with some caveats, inflation-linked bonds even offer some inflation protection. They can outperform if inflation rises and central banks fail to raise rates in response, as in 2021, when most central bankers bravely insisted that inflation was transitory. Shorter-term inflation-linked bonds can offer payouts with lower exposure to rising interest rates, a bet that can be increased with leverage if a speculator wishes. And long-term investors, such as pension funds, who hold the bonds until maturity are not much affected by fluctuations in a bond’s market price. By retaining inflation-linked cash flows, they can offset liabilities that are often also indexed to inflation.

This is a trade-off for bond issuers. The interest of pension funds and other risk-averse investors in inflation-linked bonds means that they may have to pay a premium for them. But other buyers may demand a discount because the markets for inflation-linked bonds are relatively illiquid as pension funds are not interested in selling. The empirical evidence on which the effect dominates is patchy at best. Policymakers have come to different conclusions. In 2012, an analysis by New Zealand’s Debt Management Office suggested a tenfold increase in inflation-linked bond issuance as a percentage of total issuance over the next ten years. A 2017 study for the Dutch government concluded the opposite: limited liquidity made inflation-linked bonds more difficult than useful.

There have certainly been cases where governments have saved a lot of money by issuing inflation-linked bonds. The first British bond issue in 1981 coincided with an 800-year high in British inflation. While the price reflected the expected annual inflation of 11.5%, the price ultimately paid out a realized inflation of only 5.9%. Lately, however, luck has gone in the opposite direction for Britain and most other rich world bond issuers. Soaring inflation has pushed up the coupon payments owed by governments and raised concerns about rising debt costs.

So sometimes the bond issuer will win and sometimes it will lose. But in the long run, the odds are in his favor. That’s because inflation-linked bonds shift inflation exposure from bondholders to issuers, and markets compensate those willing to take risks. Moreover, governments are well placed to accept this risk: high inflation usually means higher nominal tax revenues and more money to pay off debt.

Forget bitcoin and gold

One question remains. If not inflation-linked bonds, what should an investor worried about rising prices have held at the end of 2021? Stocks underperformed even as they recovered, as did bitcoin. However, gold and oil retained their value. It would still have been a better trade to bet on the price of falling bonds, including those linked to inflation. ■

Read more from Free Exchange, our column on economics:

Universities fail to stimulate economic growth (February 5)

Biden’s re-election chances are better than they seem (February 1)

The False Promise of Friendshoring (January 25)

For more expert analysis on the biggest stories in economics, finance and markets, sign up for Money Talks, our weekly subscriber-only newsletter.